(Original Title: Whole and Undefiled We Must Maintain the Integrity of the Catholic Faith)

Regular readers of our magazine are aware of the fact that we have frequently pointed out the errors of the so-called “Recognize and Resist” theological position — often simply referred to as R&R. The reason for our repeated warnings is because this teaching is erroneous — even heretical — and if we wish to preserve the integral Catholic Faith, pure and unadulterated, we must avoid like the plague any erroneous teachings which would undermine it. As we read in the Athanasian Creed: “Whosoever will be saved, before all things it is necessary that he hold the Catholic Faith. Which Faith, unless every one do keep whole and undefiled, without doubt he shall perish everlastingly.”

We must expose this error repeatedly in our times, since it is so frequently promoted by those who are considered by many to be orthodox proponents of the traditional Catholic Faith. As St. Paul admonishes Timothy: “Preach the word, be urgent in season, out of season; reprove, entreat, rebuke with all patience and teaching” (2 Timothy 4:2). Certain truths must be expounded over and over, especially those that are so frequently contradicted.

This is so much the more important today, since so many otherwise faithful Catholic teachers and writers constantly instill this error into their unsuspecting followers. We don’t have so much to fear from obvious heretics as we do from apparently faithful Catholics, who “as with a drop of poison, infect the real and simple faith taught by Our Lord and handed down by Apostolic tradition” (Pope Leo XIII, Satis Cognitum, par. 9). This particular error is regularly promoted in the publications Catholic Family News and The Remnant, and also by the members of the Society of St. Pius X, among others. Further, the proponents of this teaching constantly warn against “the dangers” of sede-vacantism, preventing their followers from even considering the merits of the sede-vacantist conclusion to the crisis we face today.

Just What Do Those Who Recognize the Pope but Resist Him Say?

Before we continue, I would like to explain exactly what is meant by this “Recognize and Resist” teaching and why it is erroneous. We will then go on to examine some details of Church history regarding similar errors, which paved the way for this one.

Not only is this novel idea (of accepting

a man as a true pope but defying his

decrees) completely contrary to all Catholic

Church teaching, it also leads to corollary

errors. For example, this error necessarily

deputes an individual other than the pope

to become the judge of what to obey and

what to reject.

First, it must be admitted that the phrase “Recognize and Resist” is a cumbersome title, which attempts to describe the primary error of its adherents. And what is that? It is the idea that faithful Catholics today can accept the papal claimants since Vatican II as being true popes but resist those among their teachings which they consider heretical and their disciplinary decisions which they consider dangerous or harmful. They consider themselves fully justified in rejecting doctrinal teachings and disciplinary decisions of one whom they believe to be a true pope — when they have concluded that these things are contrary to the Faith.

The problem here is that this practice is entirely contrary to traditional Catholic teaching and practice. In fact, there is no precedent in Church history for such a practice, however much its proponents try to claim some sort of precedent. Not only that, but it is flat-out opposed to various doctrinal pronouncements, especially those of the Vatican Council of 1869-1870. (Please note that this true council is now usually referred to as Vatican Council I, in order not to confuse it with the infamously heretical Vatican Council II.)

For example, Vatican I teaches as follows: “We teach and declare that the Roman Church, by the disposition of the Lord, holds the sovereignty of ordinary power over all others, and that this power of jurisdiction on the part of the Roman Pontiff, which is truly episcopal, is immediate; and with respect to this the pastor and the faithful of whatever rite and dignity, both as separate individuals and all together, are bound by the duty of hierarchical subordination and true obedience, not only in things which pertain to faith and morals, but also in those which pertain to the discipline and government of the Church spread over the whole world… This is the doctrine of Catholic truth from which no one can deviate and keep his faith and salvation” (Denzinger, 1827).

Please note carefully that anyone who refuses to submit — ”not only in things which pertain to faith and morals, but also in those which pertain to the discipline and government of the Church”— places himself outside “faith and salvation.” The matter could not be clearer. Remember also that this is not a theological opinion but the solemn teaching of an ecumenical council.

Not only is this novel idea (of accepting a man as a true pope but defying his decrees) completely contrary to all Catholic Church teaching, it also leads to corollary errors. For example, this error necessarily deputes an individual other than the pope to become the judge of what to obey and what to reject. In effect, those who follow this error become popes unto themselves, as they judge which Vatican pronouncements they will accept and which they will reject. Once again, such a practice has been anathematized by Vatican Council I: “Since the Roman Pontiff is at the head of the universal Church by the divine right of apostolic primacy, We teach and declare also that he is the supreme judge of the faithful, and that in all cases pertaining to ecclesiastical examination recourse can be had to his judgment; moreover, that the judgment of the Apostolic See, whose authority is not surpassed, is to be disclaimed by no one, nor is anyone permitted to pass judgment on its judgment” (Denzinger 1830).

Further, those who advocate this judging and “sifting” will necessarily differ among themselves as to what should be accepted and what is to be rejected, leading to disunity. For example, some are happy to accept Paul VI’s mitigated Communion fast and his other laws regarding fast and abstinence. They will, without scruple, eat meat on Fridays throughout the year, believing themselves bound to abstain only on Ash Wednesday and the Fridays of Lent. Yet at the same time, they will reject the annulments granted by the Vatican using the changes of the same Paul VI regarding grounds for marriage annulments. (Paul VI introduced the so-called “psychological” grounds for annulments, which have led to the explosion of annulments granted by the Conciliar Church.) Others, however, want to take advantage of these expanded grounds for annulments, because it suits them to do so. Numerous other examples could be given, once you open the Pandora’s Box of each person deciding for himself what to accept and what to reject.

As you can see with these few examples, this R&R mentality leads to utter chaos and widespread variation in practices of Church discipline. The Society of St. Pius X, however, attempts to keep its adherents in line by telling them to accept the judgment of their superiors regarding what should be accepted and what rejected. Thereby, they make of these superiors a quasi-papal authority.

Where did the current of resisting the Pope originate from?

The questions naturally arises, “Where did this mentality come from?” And that is a good question. Since it is so contrary to defined Church teaching and to twenty centuries of Church practice, how did it possibly gain acceptance? To answer this question, let us take a brief look at some details of Church history which show us the roots of such an error.

In the 14th century the Church faced an unprecedented crisis. Upon the death of Pope Gregory XI in April, 1378, the archbishop of Bari was elected pope at Rome and took the name Pope Urban VI. Soon after his election, however, the French cardinals disowned him. Returning to Avignon in southeastern France, they claimed that they had been forced into electing an Italian and proceeded to elect one of their own, who took the name of Pope Clement VII. Catholics were bewildered. Which one was the true pope?

This division persisted for several decades, when a group of cardinals decided to resolve it by means of a council to be held at Pisa in 1409. They denounced the two papal claimants and proceeded to elect another pope. Since neither the true pope (at Rome), nor the anti-pope in Avignon would agree to abdicate, there were now three men claiming to be pope, causing even greater confusion to the faithful. At length, a council was assembled at Constance which resolved the crisis, electing Cardinal Otto Colonna, who took the name of Pope Martin V. This election restored peace to the Church, as the other claimants were either deposed or voluntarily renounced their claim for the good of the Church. The crisis was resolved.

This unprecedented situation in the Church, however, was the source of a heretical notion called Conciliarism. Many theologians speculated that a general council was superior to a pope and had greater authority than a pope. We know that is heresy — especially since the dogmatic definitions of Vatican Council I on the papacy — but at the time it was not so clear to everyone. Interestingly, when he approved the documents of the Council of Constance, Pope Martin V carefully deleted all references to this heretical notion. Consequently, with these corrections, the Council of Constance is placed among the twenty general councils of the Catholic Church.

This notion, however, that a general council has a greater authority than the pope, persisted. The ideas of Conciliarism led to the Council of Basel, which fell apart and is not accepted as a true council of the Church. Finally, Conciliarism was condemned at the Fifth Lateran Council, held between 1512 and 1517. But this condemnation of conciliarist ideas at a true council did not completely eliminate them from the minds of all Catholics. In France, the conciliarist ideas eventually developed into another heresy called Gallicanism.

The heresy known as Gallicanism includes a group of opinions peculiar to some Catholic theologians and thinkers in France — hence the name Gallican. These ideas tended to restrain the pope’s authority in favor of that of the bishops and the temporal ruler. In 1682 a group of clergy in France came out with a declaration which detailed these ideas.

Gallicanism wished to limit papal authority by the temporal power of princes and by the authority of general councils and of the bishops, who alone (in their thinking) could give to papal decisions infallible authority. These ideas led bishops to extend their jurisdiction and civil magistrates to encroach on Church affairs. Gallicansim limited the doctrinal authority of the pope in favor of that of the bishops. The so-called “Gallican Liberties” would give the king of France authority over Church rulers. For example, they claimed that papal legates could not be sent to France without the approval of the king and that their power would be subject to him. Further, bishops could not leave France without the king’s consent. Among the most heretical ideas of the Gallicans was the teaching that it is lawful to appeal from the pope to a future council.

The question naturally comes to mind: How did these ideas arise in France? The Gallicans claimed concessions and privileges of the French monarchs, going all the way back to Pepin and Charlemagne. Some Gallican apologists even claimed that their privileges originally came from the discipline of the early Church. On the contrary, however, history demonstrates clearly that the French bishops always preserved a great respect for, and deference to, the judgment of the Holy See, to whom they appealed for final judgment. Despite this history, however, some French bishops wished to revive the suppressed teachings of Constance concerning Conciliarism. Even at the Council of Trent, there were French bishops who repeatedly championed the ideas of Conciliarism.

Although Gallican ideas faded for a time, especially with the progress of Protestantism, which denied all authority to the pope, it reasserted itself in 1663, when the Sorbonne declared that it admitted no authority of the pope over the king’s temporal dominion. In 1682 King Louis XIV assembled the clergy of France and adopted the basic premises of Gallicanism, which he sought to enforce throughout France. No one could be admitted to degrees in theology without having first maintained its theses, and it was forbidden to write anything against them. The pope vigorously denounced the Declaration of 1682 and at length the king yielded. Yet the ideas of that decree remained imbedded in the minds of many of the French clergy.

Since its advent, there have been various papal denunciations of the errors of Gallicanism, especially by Pope Pius IX. Finally, at Vatican I Conciliarism and Gallicanism received the death blow, as the council defined: “They stray from the straight path of truth who affirm that it is permitted to appeal from the judgments of the Roman Pontiffs to an ecumenical Council, as to an authority higher than the Roman Pontiff ” (Denzinger, 1830).

How Did Such an Idea Gain a Following Today?

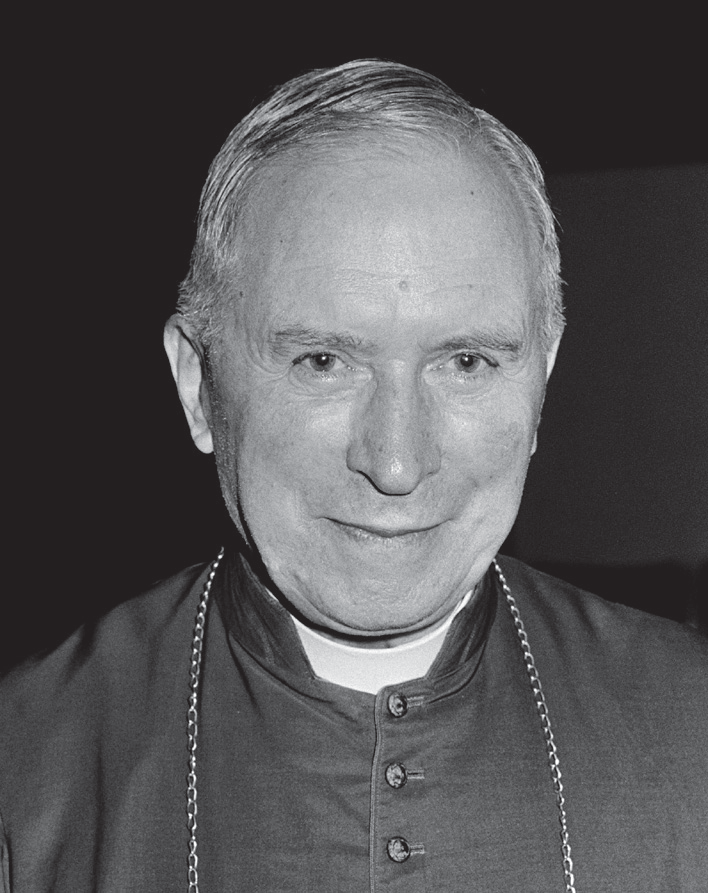

Since the teachings of the R&R ideology are so patently opposed to define Church doctrine and to the practice of Catholicism throughout history, how has it become so dominant among many traditional Catholics today? The answer is simple: because of Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre. As was the case with many Catholics, the archbishop knew that what was being promoted in the name of Catholicism since Vatican II was heretical. His sensus Catholicus revolted at the liturgical innovations, the ecumenism, the false religious liberty, etc. Yet he never could bring himself to conclude that “the pope” himself was the one responsible.

When he was suspended by Paul VI in 1976, Lefebvre believed that there was no justification for such a punishment. He simply carried on training and ordaining priests and traveling throughout the world to administer confirmation. As time went on throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the archbishop was the most prominent and well-known churchman resisting the changes. As such, he gained many adherents, including a British writer named Michael Davies, who ardently defended Lefebvre. Eventually, however, Davies came to the conclusion that he could no longer resist the one he recognized as pope and returned to full communion with the Conciliar Church.

For his part, Archbishop Lefebvre continued to waver in his mind between submission to the “pope” and the maintenance of an apostolate contra Rome. He reportedly considered the merits of sedevacantism, yet he never came to the decision of rejecting the claims of John Paul II (and his conciliar predecessors) as legitimate popes. In fact, he established a de facto parallel magisterium that carefully sifts what is taught by the purported Holy See. He continued to ordain priests and eventually consecrated bishops, in defiance of the man whom he recognized as pope.

Indeed, the “Recognize and Resist” ideology, so prevalent today in traditional circles, ought to be called Lefebvrism, as the archbishop alone is the reason why it prevails today. Was he, a Frenchman, influenced by the still latent ideas of Gallicanism and Conciliarism? We do not know, but the simple and obvious fact is that he was wrong. His theological conclusion on how to operate in this time of crisis ran counter to solemnly-defined Church teaching.

To this day, his society continues to sift the “papal” teachings. Its clergy reject the canonizations that they consider harmful or dangerous, they make a determination of which Church disciplines to follow, and they counsel their followers to accept the judgments of the society’s superiors. All of this is clearly contrary to the teachings of the Catholic Church and can in no way be justified.

In Conclusion

It is time for all those who recognize the errors that emanate from the Vatican — and in particular from the man who claims to be pope — to make a choice: either humbly submit to the man you claim is pope, or conclude that, due to his pertinacious heresy, he could not possibly be a true successor of St. Peter and therefore his claim to the papacy is to be rejected entirely. You cannot have it both ways. You especially cannot continue to follow a line of recognizing a man as pope and resisting his decrees. That is entirely un-Catholic.

Pope Pius VI denounced the idea that “the Church which is ruled by the Spirit of God could have established discipline which is …dangerous and harmful and leading to superstition and materialism” (Denzinger 1578). Yet the Novus Ordo, the new code of Canon Law and a great deal more of the discipline of the Conciliar Church is just that and even worse. It could not possibly have emanated from a truly Catholic authority.

Before concluding, let us take another look at a section of the encyclical Satis Cognitum of Pope Leo XIII, quoted at the beginning. Immediately prior to the statement concerning a “drop of poison” His Holiness states: “The Church, founded on these principles and mindful of her office, has done nothing with greater zeal and endeavor than she has displayed in guarding the integrity of the Faith. Hence she regarded as rebels and expelled from the ranks of her children all who held beliefs on any point of doctrine different from her own. The Arians, the Montanists, the Novatians, the Quartodecimans, the Eutychians, did not certainly reject all Catholic doctrine: they abandoned only a certain portion of it. Still who does not know that they were declared heretics and banished from the bosom of the Church? In like manner were condemned all authors of heretical tenets who followed them in subsequent ages… The practice of the Church has always been the same, as is shown by the unanimous teaching of the Fathers, who were wont to hold as outside Catholic communion, and alien to the Church, whoever would recede in the least degree from any point of doctrine proposed by her authoritative Magisterium” (section 9).

We do not want a partial Catholicism but, as Pope Leo XIII puts it, we want the “integrity of the faith.” Nothing else will do, for as the Athanasian Creed puts it so succinctly, “Whosoever will be saved, before all things it is necessary that he hold the Catholic Faith. Which Faith, unless every one do keep whole and undefiled, without doubt he shall perish everlastingly.”

–Taken from the Reign of Mary Quarterly Magazine, Issue 151